Have You Ever Experienced Wilderness?

“Wilderness” is a term that’s thrown about easily and often. Someone I know recently described the land behind her house as “a lot of wilderness.” What it is, is a couple of hundred acres of second-growth woodlands crisscrossed with old roads and stone walls. A hundred years ago, it was all open pasture and farmland; in 20 more years, it might be all house lots. Right now, it’s undeveloped and retuning to nature, but it’s not really wilderness.

I also once had someone describe some woodlands in Maine we were visiting as “wilderness.” I didn’t have the heart to tell him that, as he said the word “wilderness,” he was sitting on a 30-year-old logging stump in some of the most intensively managed commercial woodlands in the entire country. I’ll admit, unless you looked closely and knew what to look for, it looked pretty wild — especially to someone from an urban environment — but, again, it wasn’t wilderness.

Even the hills of Northwest Connecticut, the Berkshires of Massachusetts, most of the Green and White Mountains don’t deserve to be called “wilderness.” Some parts of the vast Adirondack Park in New York and Baxter State Park in Maine certainly do. But most parks and National Forest are managed for sustained multiple use. Wilderness is a step beyond.

Wilderness is a place that’s largely protected from human encroachment by choice or chance of geography, where the impacts of humans are minimized as much as possible. Managed woodlands just don’t count. According to the Wilderness Act of 1964, which created the original federally protected wilderness areas, a federal Wilderness is:

“…an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvement or human habitation…”

While we don’t have anything in New England or New York that matches the vast, untrammeled tracts of the northern Rockies, Alaska and northern Canada, we do have places that deserve to be called wilderness. These are all “artificial” wildernesses in the sense that they’ve been heavily used by humans in the past but have been recently protected and are being allowed to return to a more “wilderness” state. Almost 20 percent of the White Mountain National Forest is designated Wilderness. According to the AMC’s White Mountain Guide, “In general, visitors to Wilderness Areas should look forward to a rougher, wilder, more primitive experience . . .”

You can find a complete list of federal wilderness areas along with a lot of material on the history and current state of these areas at http://www.wilderness.net.

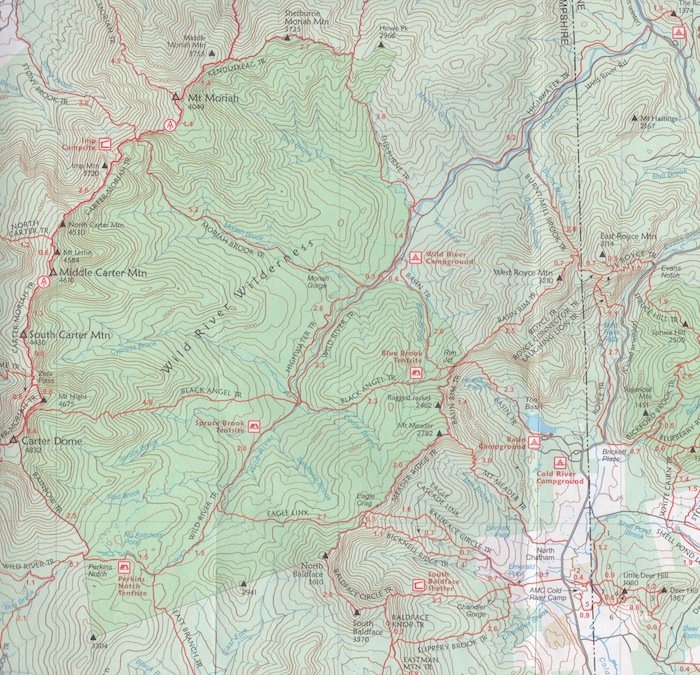

Into The Wild River Wilderness

The Wild River Wilderness a 24,000-acre parcel of White Mountain National Forest right along the Maine border on the eastern flank of the White Mountain National Forest. A while ago, in the quiet season between leaf-peeping and snow, while our wives were enjoying a weekend of what they call “retail therapy” (which I refer to as “shoot me, now”), EasternSlopes.com’s Senior Editor David Shedd and I threw light packs on our backs and headed into the wilderness. Literally.

David and I had visited this area some years ago but knew the Wild River Wilderness had grown more wild since we’d last been there. Two of the lean-to shelters at designated camp sites had been removed as part of the “without permanent improvement” that designates wilderness areas. And a bridge across the aptly-named Wild River had been washed out by Hurricane Irene. This area had been heavily logged in the 19th century and a fire in 1903 had wiped out any remaining timber and most of the infrastructure of the logging operations. You can still see the old roadbeds for the rail lines that hauled out the timber, but that’s about all you’ll see.

We’d had a couple of days of heavy rain before we parked our car at the virtually-deserted Wild River Campground, loaded on our packs and took to the trail. That rain weighed heavily on our plans, since the Wild River drains steep country and can rise surprisingly quickly to levels that make crossing it impossible.

The basic plan was to hike the Basin Trail to the Blue Brook Tentsite and overnight there. This is one of only three designated camping areas in the Wilderness. We didn’t expect much company at that time of year, even on a Saturday night. But we had a plan B: If the designated tentsite was crowded, we’d have time to bushwhack a bit and find our own spot for our two-man tent.

The next morning, we would hike over the Black Angel Trail until it met the Wild River. From there, we had three options—cross the river if we could and hike out on the “High Water Trail,” If we couldn’t get across the river, we would either take the Wild River Trail back to the car or, if that was too difficult with high water, we’d retrace our route.

A Night in the Wild River Wilderness

Turns out we were able to follow plan A. The hike in to the tentsite was pleasant and uneventful. The Basin Trail apparently gets a goodly amount of foot traffic and it was easy to follow. We met up with two other hikers as they were headed out on the Black Angel. They had been in the wilderness a couple of days and we were the first other hikers they’d seen.

The Blue Brook tent site was empty when we arrived so we took what we judged to be the prime spot. The tent sites are all within sight of each other and we hoped no one else would occupy them for the evening; wilderness is better if you don’t have to share it. Turns out, even on a Saturday night, we had the place to ourselves. As we set up camp and cooked and ate dinner, the wind started rising. It wailed above us all night like the ghost of one of those old logging trains. Occasionally, it reached down through the trees to rattle the tent.

It was frosty and still windy as we cooked breakfast and packed up the camp next morning. Some snowflakes danced in the early light. The cold made it hard to get going, but we warmed up quickly once we ate, packed up camp and hit the Black Angel trail. Lots of moose sign and several grouse rocketing away made the hike feel even more like a true wilderness experience.

Wilderness Skills Put To The Test

We wouldn’t know if we could stick to Plan A until we actually reached the Wild River. As it turned out, we were able to stick to plan, but crossing the Wild River was an interesting and delicate process of picking the right rocks to jump to. Trekking poles really help in a situation like this. In fact, they are almost essential for safety, giving you extra stability when you have to take a long step onto an uncertain surface. We both made it across dry and safe, but it was tricky in spots and with only an inch or two more water, we likely wouldn’t have tried. Crossing flowing water on a cold morning is not something to do thoughtlessly.

The High Water Trail gets less traffic that the other trails and was tough to follow in spots. Several times, the trail suddenly seemed to disappear and we had to look around a bit to make sure we were on the right track. That’s another skill you need to practice for wilderness travel. Do it enough and you develop a sixth sense that will bring you up short before you lose the trail altogether. When two or more are hiking together, the instant you sense something might be wrong, you stop. One person stays where they are, the other backtracks until they are sure they are on the trail again and stays there until the lead hiker is sure they have the trail farther on.

If you are alone, you stop, tie a piece of surveyor’s tape (from the emergency kit you always have with you) to a branch and then try to retrace your steps until you find the trail again. Be sure you pull off your emergency marker before you leave the area–this is wilderness and you want to leave no trace of your passage. And you especially don’t want someone who follows you thinking the emergency ribbon marks a trail.

A trail like the High Water is perfect from practicing this skill. If you truly lose the trail, you know approximately where the river is and can just follow along it until you either re-find the trail (probably at a side gully crossing) or at the bridge that leads to the Wild River Campground. You’d have award time getting really lost here.

But the side gullies I just mention pose another interesting challenge. There are a number of them and they all become rapidly flowing streams after a rain. They were almost as tough to cross as the river had been, so we got lots of practice with high water crossings.

But, even with these small challenges, we made good time and arrived back at the car almost exactly 24 hours after we’d left it. In fact, we were out in time to meet our wives for lunch at Delaney’s Hole In The Wall in North Conway. One full day in wilderness; a wonderful experience, infinitely better than shopping, but still not enough. You can bet we’ll be back to do more exploring when we can be pretty certain that we’ll have the wilderness to ourselves.

Just did the Highwater Trail June 2018 coming in from Rattle River and down Shelburne-Moriah. Lost the trail several times between Shelburne Junction and Moriah Brook junction – lots of it is in the river. Spent the afternoon bushwacking beyond the Moriah Brook Junction trying to find it again. Gave up, made camp almost where we’d started that morning, hung out in afternoon and all-night rain, and woke to more of the highwater trail swallowed by the river in new landslides plus plenty of new large (12″dia+) trees in the river.

The Highwater Trail is definitely wild!